Maciej Bernhardt - painting/drawing

29 April - 26 June 2022

BWA SOKÓŁ Gallery of Contemporary Art

vernissage:

29 April 2022, hour 18:00

ticket prices

Normal ticket - 5 PLN/person, Discounted ticket - 3 PLN/person, Group ticket (from 10 persons) - 2 PLN/person, Family ticket - 1 PLN/person, Every Wednesday ticket - 1 PLN/person, Ticket for anti-communist opposition activists - 1 PLN/person.

Additional information:

Gallery opening hours:

Monday: closed

Wednesday: 11.00-16.00

Tuesday, Thursday, Friday: 11.00-18.00

Saturday-Sunday: 11.00-17.00

Monday: closed

Wednesday: 11.00-16.00

Tuesday, Thursday, Friday: 11.00-18.00

Saturday-Sunday: 11.00-17.00

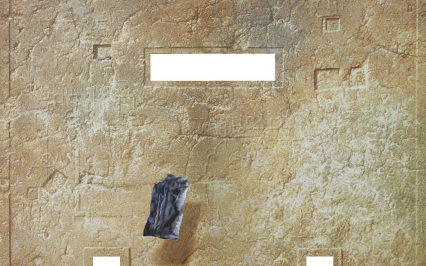

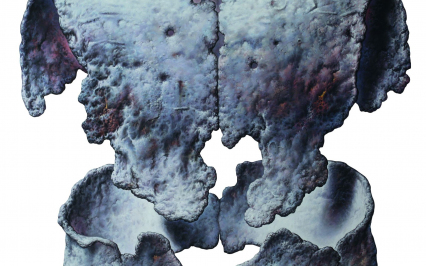

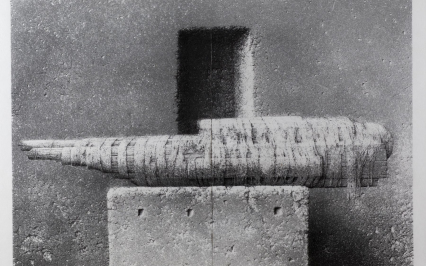

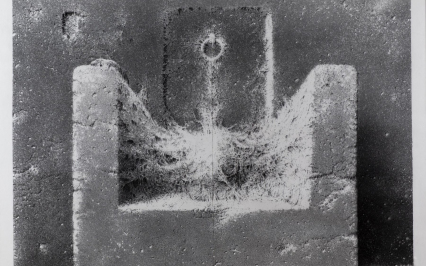

An exhibition of paintings and drawings by Maciej Bernhardt, whose works can be found in the collections of the National Museum in Krakow, in the city collections of Darmstadt, Nuremberg and Cleveland, as well as in many private collections in Germany, France, Holland, Austria, England, USA and Poland.

THE PAINTING OF MACIEJ BERNHARDT

FRANCISZEK CHMIELOWSKI

Maciej Bernhardt’s place in the panorama of contemporary art is as one of the most distinguished representatives of Photorealism. His pictures were noticed and commended by art critics already back in the 1970s, when as a freshlybaked graduate of the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, he took part in the National Art Festival in Bydgoszcz, organized under the name Artistic Fact and Reality [1]. Against the background of the plebeian art products of that time in Poland – which were guided by Socialist-Realist ideology, or else by a metaphorical resistance thereto – Bernhardt’s masterfully painted pictures represented a new quality. They drew viewers’ attention with their maturity of artistic form and the extensive scale of the meanings they bore, which moved boldly into the sphere of emotions difficult to verbalize. The aptness of these paintings’ message and their independence with respect to established thought and perception stereotypes of the time are, from today’s perspective, comparable only to the most interesting accomplishments of critical art.

In Bernhardt’s paintings of surprising artistic freshness, first of all, critics noticed their similarity to American Hyperrealism, which was justified insofar as, similarly to the case of the American achievements, what came to the fore was a manner of reflecting the world which appealed to the technical medium of photography. Another similar element was the tendency derived from pop-art to focus on the world of actually existing objects, which represented a peculiar counterweight to the onesided influence of the then dominant trends of minimal art and Conceptualism. However, a more attentive examination and perceptive analysis revealed differences as well. Insofar as for Hyperrealism, what was most important was the problem of objectively-conceived optical reality – understood as a method of artistic formation and, at the same time, an issue of agreement with the optical reality of the objects being represented – for the more broadly-conceived photorealism, the trend to which Maciej Bernhardt’s works belong, what also counted were qualities, mental aspects and associations connected with the pictorial representation which were amenable to interpretation.

Hyperrealism attempted to maintain a cool distance from the reality being presented and efface the peculiar characteristics of the painter’s individual technique. It tried to convey an impression of complete distance, an objectified and quasi-scientific approach to mechanicallyreproduced objects, which yielded an effect bordering on the irony of an Existentialist atmosphere. An example of this could the unnaturally magnified and naturalistically sharpened details of the human face in the portraits painted by Chuck Close, the framed images of automobiles in the paintings of such artists as Don Eddy or Ralph Goings, or Richard Estes’ cool views of urban architecture. Photorealism, however, was not averse to aesthetic values and attempted to maintain a humanistic warmth in its representations; one could say that its intended aim was to humanize photography and consciously transform automatic and anonymous reproduction into a spiritual, living and pulsating tissue of the painted image.

FRANCISZEK CHMIELOWSKI

Maciej Bernhardt’s place in the panorama of contemporary art is as one of the most distinguished representatives of Photorealism. His pictures were noticed and commended by art critics already back in the 1970s, when as a freshlybaked graduate of the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, he took part in the National Art Festival in Bydgoszcz, organized under the name Artistic Fact and Reality [1]. Against the background of the plebeian art products of that time in Poland – which were guided by Socialist-Realist ideology, or else by a metaphorical resistance thereto – Bernhardt’s masterfully painted pictures represented a new quality. They drew viewers’ attention with their maturity of artistic form and the extensive scale of the meanings they bore, which moved boldly into the sphere of emotions difficult to verbalize. The aptness of these paintings’ message and their independence with respect to established thought and perception stereotypes of the time are, from today’s perspective, comparable only to the most interesting accomplishments of critical art.

In Bernhardt’s paintings of surprising artistic freshness, first of all, critics noticed their similarity to American Hyperrealism, which was justified insofar as, similarly to the case of the American achievements, what came to the fore was a manner of reflecting the world which appealed to the technical medium of photography. Another similar element was the tendency derived from pop-art to focus on the world of actually existing objects, which represented a peculiar counterweight to the onesided influence of the then dominant trends of minimal art and Conceptualism. However, a more attentive examination and perceptive analysis revealed differences as well. Insofar as for Hyperrealism, what was most important was the problem of objectively-conceived optical reality – understood as a method of artistic formation and, at the same time, an issue of agreement with the optical reality of the objects being represented – for the more broadly-conceived photorealism, the trend to which Maciej Bernhardt’s works belong, what also counted were qualities, mental aspects and associations connected with the pictorial representation which were amenable to interpretation.

Hyperrealism attempted to maintain a cool distance from the reality being presented and efface the peculiar characteristics of the painter’s individual technique. It tried to convey an impression of complete distance, an objectified and quasi-scientific approach to mechanicallyreproduced objects, which yielded an effect bordering on the irony of an Existentialist atmosphere. An example of this could the unnaturally magnified and naturalistically sharpened details of the human face in the portraits painted by Chuck Close, the framed images of automobiles in the paintings of such artists as Don Eddy or Ralph Goings, or Richard Estes’ cool views of urban architecture. Photorealism, however, was not averse to aesthetic values and attempted to maintain a humanistic warmth in its representations; one could say that its intended aim was to humanize photography and consciously transform automatic and anonymous reproduction into a spiritual, living and pulsating tissue of the painted image.

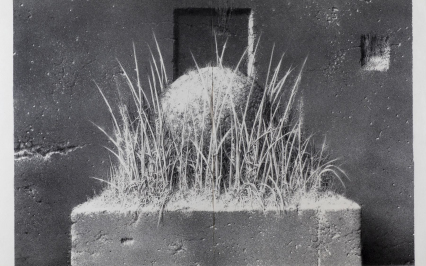

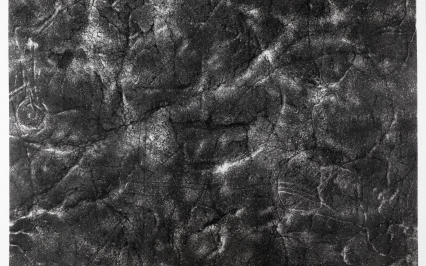

image gallery

This fundamental difference between Hyper- and Photorealism was observed by a splendid connoisseur of the subject, Louis K. Meisel, in his monumental work entitled Fotorealismus. Die Malerei des Augenblicks, in which he wrote that though both movements accent the priority of representation, they are divided by an array of important issues, such as the treatment of the image plane, the approach to aesthetic values and to the Realist painting tradition in the broad sense. Meisels also recalled that ‘the great merit of Photorealism was the reintroduction of manual skills into contemporary art. The majority of Photorealists state that during their student days, they were not introduced to the methods and techniques they use in their works; they were, on the other hand, taught abstract theories about the application of paint to canvas. In the course of their artistic career, they have had to rediscover or reinvent the painting techniques they use in practice’3. The phenomenon of restoring importance to issues of technique and manual craftsmanship skills also confirms the virtuosity of the pictures painted by Maciej Bernhardt, which not infrequently attain an artistic qualitas on a par with the old masters.

It is also interesting to note that Meisel points to different sources and artistic affiliations in the cases of Photorealism and Hyperrealism than has been recorded in popular works on the subject. Forasmuch as he agrees with the thesis of Hyperrealism’s relationship to pop-art, Photorealism (similarly to Conceptualism and process art) is in his view derived from Abstract Expressionism, in which the element of creation authorized all types of open, manifold and direct endeavors – thus, as well, aesthetic experiments associated with the manual process of painting, as well as the illusionary treatment of the image plane.

Departure from the principles and limitations of Realist art in European painting began during the times of Cézanne and the French Impressionists; it is from that time onwards, as well, that one speaks of modern art. For the next hundred years, new artistic ideas, tendencies and directions continually appeared, until the 1960s, when the Minimalists, Conceptualists and environnement artists announced the end of painting with a palette. In this manner, artists liberated themselves from the yoke of the last rule of the art of painting, which was the necessity of applying paint to a canvas. However, at the same moment, the paradox of absolute freedom became active. Since artists can presently do anything, and describe everything they do as art – then they can also apply paint to a canvas. They can do it however they like, as well as using any method or ancillary technical resources they like. The Photorealists took advantage of this opportunity and utilized it in every way, including the effective use of photography.

It is also interesting to note that Meisel points to different sources and artistic affiliations in the cases of Photorealism and Hyperrealism than has been recorded in popular works on the subject. Forasmuch as he agrees with the thesis of Hyperrealism’s relationship to pop-art, Photorealism (similarly to Conceptualism and process art) is in his view derived from Abstract Expressionism, in which the element of creation authorized all types of open, manifold and direct endeavors – thus, as well, aesthetic experiments associated with the manual process of painting, as well as the illusionary treatment of the image plane.

Departure from the principles and limitations of Realist art in European painting began during the times of Cézanne and the French Impressionists; it is from that time onwards, as well, that one speaks of modern art. For the next hundred years, new artistic ideas, tendencies and directions continually appeared, until the 1960s, when the Minimalists, Conceptualists and environnement artists announced the end of painting with a palette. In this manner, artists liberated themselves from the yoke of the last rule of the art of painting, which was the necessity of applying paint to a canvas. However, at the same moment, the paradox of absolute freedom became active. Since artists can presently do anything, and describe everything they do as art – then they can also apply paint to a canvas. They can do it however they like, as well as using any method or ancillary technical resources they like. The Photorealists took advantage of this opportunity and utilized it in every way, including the effective use of photography.

image gallery

Use of photography during painting brings numerous consequences, philosophically as well, associated with the ontology of the creative process. Photography fundamentally changes its initial phase, enabling one to make decisions essential to the picture already before commencing the act of painting. Thanks to the use of photography, the artist can more effectively focus on the problem of painted representation itself, not wasting time devising the composition, coloristic language and symbolic meanings of the picture, because all of that has already been settled during the selection of a particular picture, or the personal arrangement and taking thereof, as is the case in Maciej Bernhardt’s oeuvre. Also interesting is the fact that the Photorealists extraordinarily rarely abandon or destroy their pictures, considering them to be off the mark, during the painting process, which in the case of abstract art is an extremely frequent phenomenon. This happens for the simple reason that the Photorealist knows exactly how the finished picture is supposed to look and works on it for a very long time, sometimes for several months or even more than a year, until it corresponds with his or her imagination and expectation.

Maciej Bernhardt’s paintings are part of the modern Photorealist painting movement, while at the same time retaining individual characteristics associated with the artist’s personality and temperament, sensitivity and experience. Unlike the achievements of American Hyperrealism, Bernhardt’s pictures are not only optical ‘shots’ of reality, recording something random and basically unimportant, but represent harmoniously composed entireties of form and content whose elegant material, rich structure and complex semantic language mean that we are dealing with first-class works of art. Valuable artistic objects always belong to the category of symbols and – just like them – ‘give one something to think about’, revealing the more deeply hidden layers of meaning of the human world. Thus, it is no wonder that their significance and meaning were recognized already at the beginning of the artist’s career, when by force of imagination and determination of will, he disposed of the everyday humdrum of Socialist Realism in his own way. The cycle of pictures with political connotations is one of many; at the same time and later on, other series were also painted (e.g. Sanctuaries), focused more on metaphysical matters, engaging the need for spiritual concentration and maximal intensity of presentation.

Maciej Bernhardt’s Photorealist paintings are an extraordinary phenomenon in Polish and world contemporary art. Modern in form of presentation, they retain respect for traditional mastery. Open to a multiplicity of senses and meanings, they build their semantic language on an intensity of aesthetic experience. Against the background of increasing Post-Dadaist and Post-Conceptualist tendencies, aiming to undermine the sense of painting, they represent a strong argument in favor of its continued currency and far-from-exhausted value.

_

[1] Cf. Andrzej Skoczylas, O Sztuce Faktu [On the Art of Fact], Sztuka no. 6/5/78 (November – December 1978), p. 13.

[2] Louis K. Meisel, Fotorealismus. Die Malerei des Augenblicks, Atlantis Verlag, Lucerne 1989.

[3] Ibid., p. 22.

Maciej Bernhardt’s paintings are part of the modern Photorealist painting movement, while at the same time retaining individual characteristics associated with the artist’s personality and temperament, sensitivity and experience. Unlike the achievements of American Hyperrealism, Bernhardt’s pictures are not only optical ‘shots’ of reality, recording something random and basically unimportant, but represent harmoniously composed entireties of form and content whose elegant material, rich structure and complex semantic language mean that we are dealing with first-class works of art. Valuable artistic objects always belong to the category of symbols and – just like them – ‘give one something to think about’, revealing the more deeply hidden layers of meaning of the human world. Thus, it is no wonder that their significance and meaning were recognized already at the beginning of the artist’s career, when by force of imagination and determination of will, he disposed of the everyday humdrum of Socialist Realism in his own way. The cycle of pictures with political connotations is one of many; at the same time and later on, other series were also painted (e.g. Sanctuaries), focused more on metaphysical matters, engaging the need for spiritual concentration and maximal intensity of presentation.

Maciej Bernhardt’s Photorealist paintings are an extraordinary phenomenon in Polish and world contemporary art. Modern in form of presentation, they retain respect for traditional mastery. Open to a multiplicity of senses and meanings, they build their semantic language on an intensity of aesthetic experience. Against the background of increasing Post-Dadaist and Post-Conceptualist tendencies, aiming to undermine the sense of painting, they represent a strong argument in favor of its continued currency and far-from-exhausted value.

_

[1] Cf. Andrzej Skoczylas, O Sztuce Faktu [On the Art of Fact], Sztuka no. 6/5/78 (November – December 1978), p. 13.

[2] Louis K. Meisel, Fotorealismus. Die Malerei des Augenblicks, Atlantis Verlag, Lucerne 1989.

[3] Ibid., p. 22.