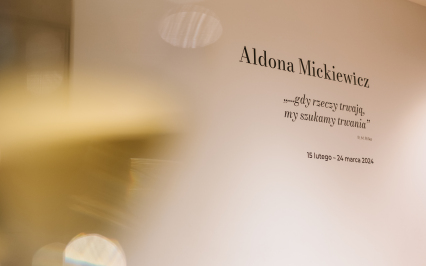

"...when Things last, lasting we seek"

15 February - 24 March 2024

Gallery of Contemporary Art BWA SOKÓŁ

vernissage:

15 February 2024, hour 18:00

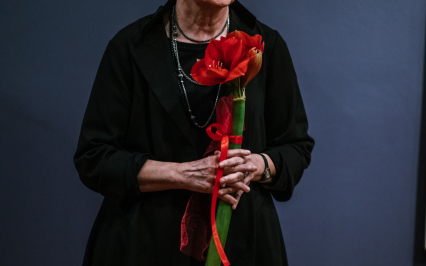

The exhibition of Aldona Mickiewicz's work, bearing a title taken from Rainer Maria Rilke's poetry, shows viewers the iconic works of Mickiewicz, an acclaimed artist reaching mastery in still life painting.

The process of painting still life on the basis of some objects arranged in front of the easel as some sort of an altar to which an artist devotes all her or his attention is a unique phenomenon – characterized by a tint of anachronism and a large dose of romantic melancholy. This motif is still popular as it seems to be a very effective way of creating a bond with the surrounding reality, sinking into it, entering its structure in order to grasp and become familiar with the essence of things – to struggle through the process of deconstruction and to build it anew on the canvas. Practicing mindfulness and being “here and now” is the art known to artists since time immemorial.

The veristic painting of still life is a bipolar experience – at the same time ecstatic and painful, satisfying and unbearable. The greedy preoccupation with details, analyzing their every particle, discovering the minutest fissures in reality, and then transferring the whole impression onto the canvas may adopt a form which can be tender or angry, or somewhere between these two emotions – depending on various factors affecting the painter’s condition on a specific day, but also the artist’s belief that what they are doing makes sense. What does, then, constitutes sense for Aldona Mickiewicz?

The artists does not focus on random objects - she profusely uses the symbolic reservoir, choosing the most meaningful objects, related to religious rites or the death and passing phenomenon – as they are timeless and universal. She retains a strong bond with the Baroque painting tradition, in which still life, representing vanitas occupied a prominent position, and trompe l’oeil enjoyed particular popularity, with the Counter-Reformation assumptions affecting the wealth and theatricality of representations. Mickiewicz, however, does not arrange still life in refined, dynamic and abundant compositions. She places objects in a simple way and does not use any embellishing techniques – as if she wanted to document, precisely and faithfully, the decay stage, to catalogue it “as it is”, time-worn. She sometimes juxtaposes them, as if she wanted to hold some sort of durability contest – a nest of wild bees found in the attic, a stone, some organic remains (wings) – their time gets even in the painting. All fabrics and clothes are turned inside out, gutted, folded – the artists wants to show what is hidden, to reveal what is not representative. Mickiewicz treats the objects with insight and empathy – the greater they are, the more pain and destruction a particular object carries with itself – in her painting she pays homage to those worn-out life assistants, which offer key support to our existence.

An interesting category is objects directly related and touching human body – crumpled clothes and bed linen, and even, as in the Et in Arcadia ego cycle – masks and forms taken off human body, used in radiotherapy (associated with the skull from Guercin’s painting from around 1622), which constitute a specific immobilizing “exoskeleton” during the exposure session. In this way the artist speaks of human corporality without showing it at all. And speaking of casting forms, her paintings, consisting of presentations of objects surrounding human body, are like negatives for body positives – they reflect its shape, describe it, but they do not contain it – they emphasize its lack. This ambivalence is strongly perceptible in Mickiewicz’s paintings – on the one hand, her paintings are rich and full (objects fulfilling the whole area, often largely rescaled), on the other hand, we can notice their incredible silence and emptiness – timelessness, an abyss of another dimension in which there are no people, but only their traces and evidence, as relics or fetish. They maintain the “idea” of a person, long after the person is gone.

Mickiewicz’s paintings are dominated by motifs adopted from Christian iconography. Her works seek religious transcendence, and she treats the act of painting as a persistent prayer or meditation. The artist uses Old Testament motifs (Scala Mistica from 1993, Steps from 1992 – paintings clearly relating to the motif of Jacob’s Ladder; Bethesda Pond from 2020, interpreted by means of kitchen utensils), hagiographic ones (Attributes cycle, showing emblems of saints), in Arma Christi cycle she – obviously – deals with the Tools of the Passion of Christ. She also likes the motifs connected with mystic visions – the exhibition has a painting titled Pascal’s Jacket from 2009 (and a drawing with the same title from 2003), showing the lining of the outer garment with a piece of paper stuck into it – the author of the famous bet never parted with a note he made after experiencing a mystic revelation and till the end of his life he sewed this Keepsake into his coats.

The artist is particularly interested in liturgy attributes, the so-called paraments – chasubles, stoles, textiles and accessories used by the altar. In this category of presentations we can distinguish the artist’s fascination, though it is difficult to classify. On the one hand we have the painter’s “food” in the form of elaborate embroidery and gilding, whose glitter fades (again, Kohelet’s vanitas), on the other hand we cannot help wondering whether the aspect of being a woman-artist is important when compared to such deep study of the matter dedicated only and exclusively to male priests?

“Feminine”, and definitely “feminist” are not the first epithets that come to our mind when we want to describe Mickiewicz’s art in a nutshell. The artist though, with her natural sensitivity and subtlety, using metaphors and avoiding literality, sometimes touches these issues. The parament cycles draw our attention and pay tribute to the quiet and persistent work of a lot of women (nuns) on elaborate ritual robes. “Menopause” from 2008 shows a battered mattress with holes, long past its prime time. The painting titled “Gutted” presents a pillow with feathers flying from it, which implies exploitation. Mickiewicz is also an author of the painting titled “Three periods in a man’s life” (2003), which corresponds with the popular motif of three periods in a woman’s life. The author thus initiates a dialogue with oppressive social reality. Her art, however, is brilliantly reserved rather than ostentatiously dealing with emotions or shouting out manifestos. The artist uses her personal biography, but even in this case this leads to dealing with a specific object in order to emphasize its weight and individual history (as in the “Ark” cycle and the “Folded” painting – showing a steel bathtub and a duvet, brought from Borderland by the artist’s repatriated family, which she used in her childhood).

The power of expression of Mickiewicz’s paintings would not be possible without deep knowledge and mastery of painter’s alchemy developed over years of consistency and freedom from haste and temporariness. Thanks to this the artist is able to use paint in such a convincing manner that we are able to see dust on the objects she paints, we see how tired and worn-out they are, how they are deprived of vitality. In addition to the form on the canvas, the artist gives then subjectivity – we look at them, but they, in complete silence, look at us, too.

Alicja Gołyźniak

The veristic painting of still life is a bipolar experience – at the same time ecstatic and painful, satisfying and unbearable. The greedy preoccupation with details, analyzing their every particle, discovering the minutest fissures in reality, and then transferring the whole impression onto the canvas may adopt a form which can be tender or angry, or somewhere between these two emotions – depending on various factors affecting the painter’s condition on a specific day, but also the artist’s belief that what they are doing makes sense. What does, then, constitutes sense for Aldona Mickiewicz?

The artists does not focus on random objects - she profusely uses the symbolic reservoir, choosing the most meaningful objects, related to religious rites or the death and passing phenomenon – as they are timeless and universal. She retains a strong bond with the Baroque painting tradition, in which still life, representing vanitas occupied a prominent position, and trompe l’oeil enjoyed particular popularity, with the Counter-Reformation assumptions affecting the wealth and theatricality of representations. Mickiewicz, however, does not arrange still life in refined, dynamic and abundant compositions. She places objects in a simple way and does not use any embellishing techniques – as if she wanted to document, precisely and faithfully, the decay stage, to catalogue it “as it is”, time-worn. She sometimes juxtaposes them, as if she wanted to hold some sort of durability contest – a nest of wild bees found in the attic, a stone, some organic remains (wings) – their time gets even in the painting. All fabrics and clothes are turned inside out, gutted, folded – the artists wants to show what is hidden, to reveal what is not representative. Mickiewicz treats the objects with insight and empathy – the greater they are, the more pain and destruction a particular object carries with itself – in her painting she pays homage to those worn-out life assistants, which offer key support to our existence.

An interesting category is objects directly related and touching human body – crumpled clothes and bed linen, and even, as in the Et in Arcadia ego cycle – masks and forms taken off human body, used in radiotherapy (associated with the skull from Guercin’s painting from around 1622), which constitute a specific immobilizing “exoskeleton” during the exposure session. In this way the artist speaks of human corporality without showing it at all. And speaking of casting forms, her paintings, consisting of presentations of objects surrounding human body, are like negatives for body positives – they reflect its shape, describe it, but they do not contain it – they emphasize its lack. This ambivalence is strongly perceptible in Mickiewicz’s paintings – on the one hand, her paintings are rich and full (objects fulfilling the whole area, often largely rescaled), on the other hand, we can notice their incredible silence and emptiness – timelessness, an abyss of another dimension in which there are no people, but only their traces and evidence, as relics or fetish. They maintain the “idea” of a person, long after the person is gone.

Mickiewicz’s paintings are dominated by motifs adopted from Christian iconography. Her works seek religious transcendence, and she treats the act of painting as a persistent prayer or meditation. The artist uses Old Testament motifs (Scala Mistica from 1993, Steps from 1992 – paintings clearly relating to the motif of Jacob’s Ladder; Bethesda Pond from 2020, interpreted by means of kitchen utensils), hagiographic ones (Attributes cycle, showing emblems of saints), in Arma Christi cycle she – obviously – deals with the Tools of the Passion of Christ. She also likes the motifs connected with mystic visions – the exhibition has a painting titled Pascal’s Jacket from 2009 (and a drawing with the same title from 2003), showing the lining of the outer garment with a piece of paper stuck into it – the author of the famous bet never parted with a note he made after experiencing a mystic revelation and till the end of his life he sewed this Keepsake into his coats.

The artist is particularly interested in liturgy attributes, the so-called paraments – chasubles, stoles, textiles and accessories used by the altar. In this category of presentations we can distinguish the artist’s fascination, though it is difficult to classify. On the one hand we have the painter’s “food” in the form of elaborate embroidery and gilding, whose glitter fades (again, Kohelet’s vanitas), on the other hand we cannot help wondering whether the aspect of being a woman-artist is important when compared to such deep study of the matter dedicated only and exclusively to male priests?

“Feminine”, and definitely “feminist” are not the first epithets that come to our mind when we want to describe Mickiewicz’s art in a nutshell. The artist though, with her natural sensitivity and subtlety, using metaphors and avoiding literality, sometimes touches these issues. The parament cycles draw our attention and pay tribute to the quiet and persistent work of a lot of women (nuns) on elaborate ritual robes. “Menopause” from 2008 shows a battered mattress with holes, long past its prime time. The painting titled “Gutted” presents a pillow with feathers flying from it, which implies exploitation. Mickiewicz is also an author of the painting titled “Three periods in a man’s life” (2003), which corresponds with the popular motif of three periods in a woman’s life. The author thus initiates a dialogue with oppressive social reality. Her art, however, is brilliantly reserved rather than ostentatiously dealing with emotions or shouting out manifestos. The artist uses her personal biography, but even in this case this leads to dealing with a specific object in order to emphasize its weight and individual history (as in the “Ark” cycle and the “Folded” painting – showing a steel bathtub and a duvet, brought from Borderland by the artist’s repatriated family, which she used in her childhood).

The power of expression of Mickiewicz’s paintings would not be possible without deep knowledge and mastery of painter’s alchemy developed over years of consistency and freedom from haste and temporariness. Thanks to this the artist is able to use paint in such a convincing manner that we are able to see dust on the objects she paints, we see how tired and worn-out they are, how they are deprived of vitality. In addition to the form on the canvas, the artist gives then subjectivity – we look at them, but they, in complete silence, look at us, too.

Alicja Gołyźniak