The Breath of Time | online

1 December 2020 - 18 January 2021

BWA SOKÓŁ Gallery

Additional information:

Online exhibition

An online exhibition of pastel painting by Jan Wagner, A Dutch artist, winner of the Award of the Programme Board of BWA SOKÓŁ Gallery of Contemporary Art at 7th International Biennial Pastel Exhibition – Nowy Sącz 2018, in the form of an individual exhibition at the BWA Gallery.

Jan Wagner

Born in the Hague (the Netherlands) in 1940. In 1962, he graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Rotterdam and, in 1982, from the Faculty of Art History, University of Amsterdam. Member of the Pictura Drawing Society in Dordrecht and Arti-shock Artists’ Association in Rijswijk. He has had several solo exhibitions in the Netherlands, among others: “Requiem” at Teekengenootschap Pictura in Dordrecht, 2009, “Water, stad en Land” at Galerie Kralingen in Rotterdam, 2017, “Vergankelijkheid” at Galerie V’-Arts in Rotterdam, 2018. He participated in several group exhibitions, among others: “Het Lied Der Achttien Dooden”, Galerie Kralingen in Rotterdam, 2015, 5th International Biennial Pastel Exhibition, Nowy Sącz, 2011. He is the winner of the Arti-shock Artists’ Association Award, Honorary Award at the 5th International Biennial Pastel Exhibition, Nowy Sącz, 2010.

photo Jan Mattheus de Grauw

photo Jan Mattheus de Grauw

movie

The artist talks about the creative process and sources of inspirations for work in an interview with his longtime friend Jan Mattheus de Grauw at his studio in Rotterdam.

Text: Andrzej Biernacki

AN ANXIOUS OBJECT

This was the title under which in the mid–1960s, a leading American art critic, Harold Rosenberg published a collection of essays, in which he decided to somewhat appraise the fashion that was prevalent at that time among top experts, critical circles and the so–called ”avant–garde audience”, namely, that of modelling themselves snobbishly on every ”novelty” in art. Rosenberg revealed the mechanism that led to this, unequivocally stating that today’s creator was no longer able to escape the constant pressure of the elite environment, which clearly dictated to him what to do. ”The awareness of the course of history,” he wrote, ”rules the art of our time and is the key to what the world’s galleries are offering at the moment. This awareness not only determines the status of new works and the conditions under which they are evaluated and acquired, but also the impulses that permeate the creative process itself and the aesthetic meaning of the thing that is being created.”Thus, based on observations resulting from his participation in the world’s art crucible, already half a century ago, this critic concluded that there is some kind of blackmail happening here: if the artist wants to be visible, he/she cannot rely on traditional assessments of values and content himself /herself with meeting the existing formal requirements, because the so–called progressive criticism together with ”avant–garde audience” led on its leash, blasé and dulled by a long series of social shocks, are no longer able to generate a deeper experience in themselves on this traditional base. And that while the artist, lacking in his repertoire the means effective enough to shake today’s audience in order to stay in the game, is increasingly willing to reach for ideas and tricks which are absurd in their essence, or even worse, because they originate from an arsenal requiring desperately weak skills, noisy and vulgar, making up creative defeatism from which – in the name of rapid marketing of goods – specialists in the top and the masses, made a virtue.

I am writing about it to outline the general conditions and the context in which, at the beginning of the 21st century, the BWA SOKÓŁ Gallery of Contemporary Art, the organizer of the Nowy Sącz Pastel Biennale came up with the reckless idea of setting up its own, as if by design ultra– traditional contest. Especially since the contest has an international out reach, and therefore all the more betraying a bold ambition of, if not stopping, than at least correcting the direction of the above–described matters. The contest whose essence is absolutely opposite to Rosenberg’s intuitions, which have intensified in the meantime, and which lies in revealing and manifesting artistic attitudes, based on individual predispositions and personal experience on the basis of the medium which dates back to the 15th century.

gallery

gallery

Undoubtedly, this age–old pastel technique has already been repeatedly and exhaustively described. Almost all of these descriptions included a time–honoured statement that pastels are an ideal way to make a visual statement, combining predispositions for both drawing and painting of an artist selecting this medium. That the uniqueness of pastels is contingent on the manner of applying the pigment on the ground whose texture can be used in the aesthetic plan of the work, which is rare in case of other media. These descriptions of what pastels can achieve have always emphasized a wide range of effects, both in terms of the visual nature of the trace and the extremely diverse ability to influence the emotions of viewers. All this is of course, true, although it seems that what distinguishes pastels in a special way from other techniques of artistic persuasion is the fact that already at the stage of the decision to choose this medium, as in no other case, the artistic INTENTION of the creator is revealed.

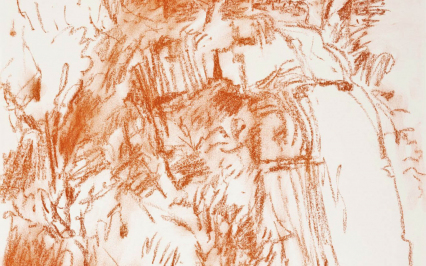

Simply put: someone who reaches for pastels declares at the outset his/her expressive intentionality of making such a choice, even, and perhaps especially, when he/she takes into account the versatility of their capabilities, including the ability to imitate other techniques. Although Jan Wagner, a Dutch participant of several editions of the Pastel Biennale in Nowy Sącz, shaped his outstanding works in the times summarized and brutally reviewed by Harold Rosenberg, he turned out to be completely immune to this kind of danger. From the beginning, he has gone his own way, focused only on what he has to convey, faultlessly finding the most appropriate means to express it. If it’s the pastel technique, Wagner will choose pastel even if the choruses of the new breed of critics are to thunder about this medium’s alleged anachronism. He is absolutely right in his conviction that it is completely irrelevant whether tools and means of creation are traditional or not because what really matters is only ... how they are used.

Simply put: someone who reaches for pastels declares at the outset his/her expressive intentionality of making such a choice, even, and perhaps especially, when he/she takes into account the versatility of their capabilities, including the ability to imitate other techniques. Although Jan Wagner, a Dutch participant of several editions of the Pastel Biennale in Nowy Sącz, shaped his outstanding works in the times summarized and brutally reviewed by Harold Rosenberg, he turned out to be completely immune to this kind of danger. From the beginning, he has gone his own way, focused only on what he has to convey, faultlessly finding the most appropriate means to express it. If it’s the pastel technique, Wagner will choose pastel even if the choruses of the new breed of critics are to thunder about this medium’s alleged anachronism. He is absolutely right in his conviction that it is completely irrelevant whether tools and means of creation are traditional or not because what really matters is only ... how they are used.

gallery

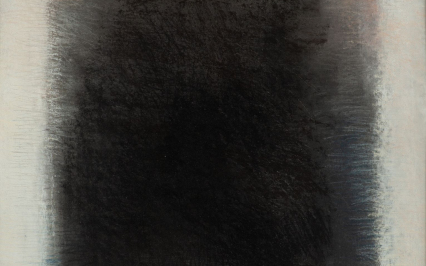

And so, it is as difficult to imagine the demise of painting, until we discover the possibility of executing it using another way, other than the traditional one, as it is difficult to imagine the uniqueness of Wagner’s visual effects, achieved in a different way, other than the pastel technique. Of course, the sketchiness, the naturalness of his earlier, semi – realistic watercolour attempts, worked great in their airy ambiguity of stains, but in the works executed in pastels, this ambiguity, very desirable in the work of art, is achieved by the artist who respects additional possibilities of expression. This includes primarily intersecting of amorphous patches, thickening and thinning out of directional lines (dashes) or juxtaposing different shades and different transparency of one colour. This effect, especially manifest in the recent series of Wagner’s work (Grafstein –Tombstone), in which, on principle and it seems finally, the painter abandons associations with emblems of the glitter of the earthly existence (as in the earlier series ”Castles”, ”Crowns”), in favour of the eschatological meaning of the sign of the crucifix. Initially, clearly stripped with the value of almost absolute black, and then increasingly less accented, acting as an attribute of a tombstone slab. This series reveals the creator’s exceptional predisposition to an apt abbreviation, the most desirable variation of the succinctness of expression, which is achieved not by the predetermined theoretical assumption, but only a posteriori, through the technical reduction of unnecessary elements, not contributing to the compositional and semantic wholeness.

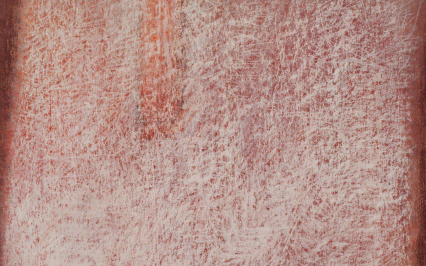

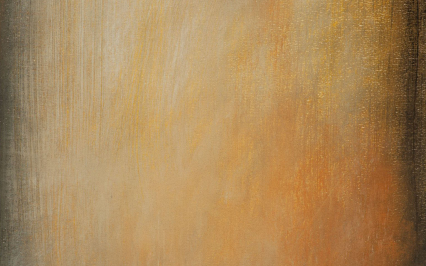

Perhaps that’s why Jan Wagner’s works, despite the lightness of the imposition of intense, sometimes even glowing vibrating tones, are characterized by a rare mood of seriousness and calm. The mood that allows you to trust the author that he is not guided by any seasonal dazzle, but only by years of talented thoughts, focusing on important and not always glamorous matters. You can see that Wagner promotes a dialogue with this tradition, which does not have to be visibly popular, but which he himself appreciates most – the one whose brand is simplicity and mystical, almost Pompeian beauty. The composition of his objects is felt with such absolute sensitivity to the slightest vibrations of the pigment that its individual components acquire monumental characteristics, despite the small size of the works. This is expressed, among other, in his ability to apply a border, which in some of his realizations like a frame encircles the arrangement on each side, emphasizing the integrity of the elements inside the painting, and at other times, with just a fragment of a border, exposes the arbitrariness of the author’s references in the frame of the rectangle of the base sides. Through such treatment, without any additional acrobatics, paintings gain each time different dynamic tension, a different mood and meaning. Each of them has its own dominant: there is the red one, the green one, the yellow one, the blue one, or the black one. The differences are determined by the luminosity and watchful determination of the proportions of colour areas. At the same time, the famous rule that two colours always match each other and only the third decides, does not apply here. Wagner’s painting may be successfully executed using a single colour but in a sophisticated and accurate combination of its various hues. In the most successful cases, these works are no longer an illustration of the theme announced by the title, but they are transformed into evocating abstract symbols. Wagner’s latest works are simply painting and they do not attempt to be anything else. They are a colourful interpretation of phenomena that everyone looks at, but does not notice, or does not understand the essence of their relationships.

Perhaps that’s why Jan Wagner’s works, despite the lightness of the imposition of intense, sometimes even glowing vibrating tones, are characterized by a rare mood of seriousness and calm. The mood that allows you to trust the author that he is not guided by any seasonal dazzle, but only by years of talented thoughts, focusing on important and not always glamorous matters. You can see that Wagner promotes a dialogue with this tradition, which does not have to be visibly popular, but which he himself appreciates most – the one whose brand is simplicity and mystical, almost Pompeian beauty. The composition of his objects is felt with such absolute sensitivity to the slightest vibrations of the pigment that its individual components acquire monumental characteristics, despite the small size of the works. This is expressed, among other, in his ability to apply a border, which in some of his realizations like a frame encircles the arrangement on each side, emphasizing the integrity of the elements inside the painting, and at other times, with just a fragment of a border, exposes the arbitrariness of the author’s references in the frame of the rectangle of the base sides. Through such treatment, without any additional acrobatics, paintings gain each time different dynamic tension, a different mood and meaning. Each of them has its own dominant: there is the red one, the green one, the yellow one, the blue one, or the black one. The differences are determined by the luminosity and watchful determination of the proportions of colour areas. At the same time, the famous rule that two colours always match each other and only the third decides, does not apply here. Wagner’s painting may be successfully executed using a single colour but in a sophisticated and accurate combination of its various hues. In the most successful cases, these works are no longer an illustration of the theme announced by the title, but they are transformed into evocating abstract symbols. Wagner’s latest works are simply painting and they do not attempt to be anything else. They are a colourful interpretation of phenomena that everyone looks at, but does not notice, or does not understand the essence of their relationships.